Laura Knight 1877-1970

In February 1946, exhausted, Knight returned home for a week’s ‘peace’, only to find her presence at the Trials a popular topic in the press, particularly after transmission of her BBC recording from Nuremberg. She had originally intended to turn her Nuremberg drawings into a painting back in England, but after recognising the need to work on the spot, had the large canvas for the final picture transported to Nuremberg. There, she was given a more spacious office room to spread out her drawings with her name and “Do not disturb” on the door. On 12th March she wrote to Harold, ‘I am trying out my rather crazy idea which gives me an opportunity for space and mystery. I do hope so much I can bring it off ... I will not say what the idea is, only that it is not normal’.

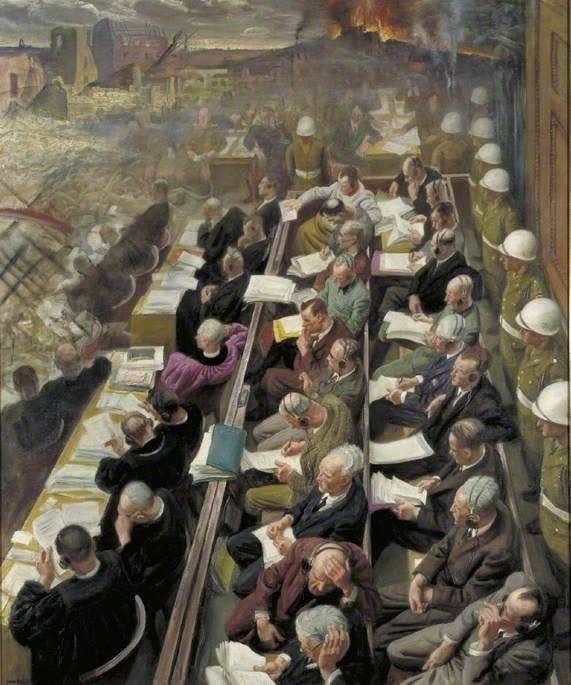

Knight’s final painting combines elements of her meticulous realist style in her depiction of the courtroom and its inhabitants, together with an act of artistic imagination unique in her oeuvre. On the right, two benches of the accused stretch away from the foreground to the centre of the painting. In front of them are two rows of black-clad lawyers, studying or shuffling reams of paper and behind and to the side, the line of Snowdrops, faithfully guarding the benches and separating the prisoners from the court beyond. In the background, the walls of the courtroom have dissolved to reveal the war torn city and burning horizon beyond. Deeply disturbed by what she heard during the trial, Knight’s apocalyptic landscape represents both the shared nightmare of war and the terrible consequences of totalitarian power. As Barbara Morden has observed: ‘It testifies to all the homes, communities, towns, cities and nations that had been dislocated and destroyed by the men in the dock. And those same men, quite ordinary in appearance, testify to the capacity of human beings to commit such atrocities that the moral, cultural and geographical fabric of not just Europe but the whole globe was polluted and broken. The painting of Nuremberg then takes on a profound universal significance. It also bears witness to the painter’s own seared conscience.’

On her return, Knight noted in a letter to the WAAC that she had never made ‘a bigger effort’ with a painting. Yet when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in London in May 1946, she was disappointed by the anti-climatic response. Some criticised the painting’s imaginative component, while others were simply ‘war weary’ and wished to move on. The artist remained proud of her work. The painting and the two drawings in the current show were exhibited together at her Paintings and Drawings exhibition at the Grosvenor Galleries, London in October 1963 (see photograph) and the studies were included in her major retrospective at the Royal Academy in July 1965.

This painting is recorded in John Croft’s Catalogue Raisonné as #0712.